off the grid: retro t.o. caribana turns 20

This installment of my "Retro T.O." column for The Grid was originally published on July 31, 2012.

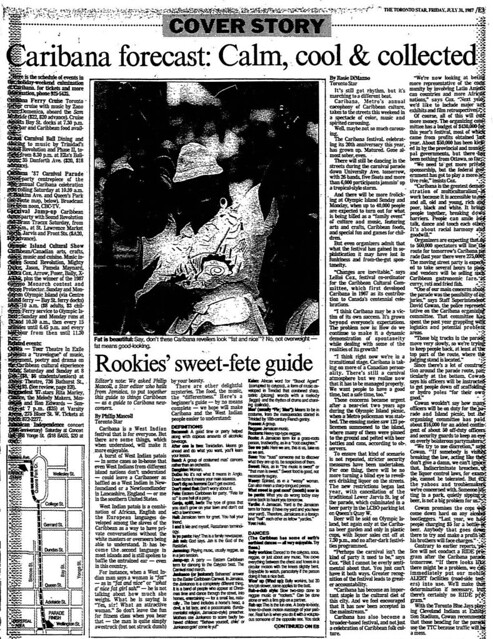

To those attending festival events for the first time or who weren’t versed in the cultures it celebrated, Star editor and Jamaica native Philip Mascoll offered several primers on etiquette, food, and language. He reassured the ladies that anyone who called them “fat” was complimenting their beauty and not poking fun at their waistline. “Ganja” (and its associated terms “spliff” and “herb”) was defined as “the type of grass that you don’t grow on your lawn and don’t cut with a lawnmower.” As for “in your pants,” readers were warned that “this is a family newspaper.”

Mascoll also offered a lengthy series of dos and don’ts to maximize parade enjoyment. Spectators were encouraged to mingle and introduce themselves to strangers, as “there is nothing to be afraid of. A large group of black people may appear to be strange and foreign to some insecure people, but except for being nicer, we are just like anyone else.” Trying to speak Caribbean patois when you normally didn’t was a bad idea, as “it makes you seem as if your elevator doesn’t go all the way to the top and annoys the listener.” Dancing in the streets and copying the moves of others was good; groping and openly drinking less so.

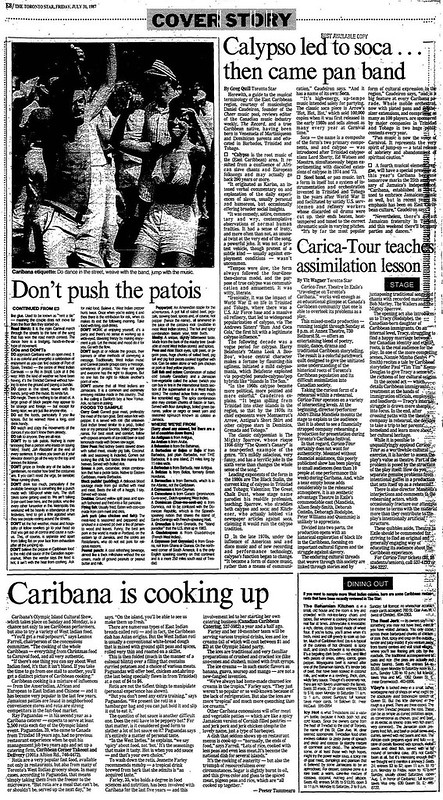

To minimize alcohol-fueled problems, safety measures introduced the previous year continued. The parade route, which started at Queen’s Park, was curtailed at University and Wellington instead of proceeding to a drink-fueled party at the LCBO parking lot off Queen’s Quay. At the annual picnic on Olympic Island, where police were pelted with beer cans and bottles in 1985, suds were only available before 7:30 p.m. in the official beer garden and in plastic cups. Still, unless revellers were truly obnoxious, police tended to overlook open drinking on parade day.

The parade itself was a record-setter. After drawing 275,000 people the year before, organizers predicted 500,000 would show up in 1987. Their guess was correct: The crowds were so thick, especially south of Dundas Street, that police and parade marshals urged spectators to stand back so that the 26-band procession could move. Police gave up maintaining the steel barriers dividing the procession from onlookers, especially since the crowd was well-behaved. As staff-superintendent Dave Cowen observed, “We’ve had less problems here than at a Blue Jays game.” Attendees were impressed by the eight-hour spectacle: “It’s absolutely glorious,” noted 73-year old Downsview resident Goldie Caesar. “It just jiggled you out of your skin it was so invigorating.” Retired life-insurance broker Jack Stern told the Star that “you could be half-dead and once this music gets in your blood then you’re alive again.”

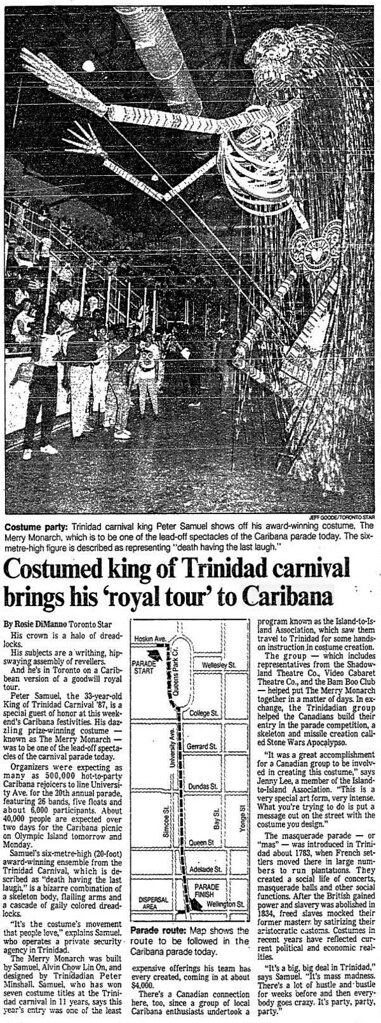

Among the parade’s special guests was Peter Samuel, the King of that year’s carnival celebration in Trinidad. His outfit, a 20-foot-high skeletal figure with flailing arms and colourful dreadlocks dubbed “The Merry Monarch,” was designed by award-winning mas-band costume producer Peter Minshall. It was partly assembled by a group of Toronto carnival enthusiasts who visited Trinidad to receive hands-on instruction in costume-making and who used the parade as a means of social commentary.

While such costumes were meant to be enjoyed outdoors, their bulk was problematic during events held inside Varsity Arena. “Inside, it’s hot and stuffy with all the body heat,” 12-year-old Camille Noel told the Star during the Junior Carnival. While she endured the heat and humidity when dressed as a snowflake (complete with leotard, fake fur, and heavy plastic), others fainted or suffered headaches. One person who kept cool was Ontario Premier David Peterson, who was provided with industrial-strength fans while attending the King and Queen of the Bands contest. In between playing coy with the media over an impending election call, Peterson told the audience in the arena that “I’ve been to Trinidad and Caribana is better here than it is there!”

Organizers admitted that, with maturity, Caribana might have lost some of its funky, spontaneous spirit. The problem was finding ways to keep that spirit while addressing growing pains. “There’s still a carnival atmosphere,” Cox told the Star, “but we realize now that it has to be managed properly.” One vow organizers made was to keep the parade free of charge to attendees—while an admission fee had once been discussed, it was determined the potential revenue stream would violate the festival’s tradition of openness. Caribana “has to be open in the streets and everyone has to participate in it,” observed lawyer Charles Roach, one of the festival’s founders in 1967. “It cannot be put in any kind of venue. That would go against a basic philosophy of the carnival spirit. Caribana is about freedom.”

Additional material from the August 3, 1987 edition of the Globe and Mail, the July 23-29, 1987 edition of Now, and the July 27, 1987, July 31, 1987, August 1, 1987, and August 2, 1987 editions of the Toronto Star.

|

| Toronto Star, July 31, 1987. |

“Caribana has become an important staple in the cultural diet of this city. And we feel encouraged that it has now been accepted in the mainstream.” Those words from festival coordinator LeRoi Cox reflected the confidence organizers felt as Caribana (the predecessor to the current Scotiabank Caribbean Carnival) celebrated its 20th anniversary in 1987. Rather than headlines reflecting fears of violence and criminal activity, coverage during that landmark year highlighted how to enjoy it.

|

| Toronto Star, July 31, 1987. Click on image for larger version. |

Mascoll also offered a lengthy series of dos and don’ts to maximize parade enjoyment. Spectators were encouraged to mingle and introduce themselves to strangers, as “there is nothing to be afraid of. A large group of black people may appear to be strange and foreign to some insecure people, but except for being nicer, we are just like anyone else.” Trying to speak Caribbean patois when you normally didn’t was a bad idea, as “it makes you seem as if your elevator doesn’t go all the way to the top and annoys the listener.” Dancing in the streets and copying the moves of others was good; groping and openly drinking less so.

|

| Toronto Star, July 31, 1987. Click on image for larger version. |

To minimize alcohol-fueled problems, safety measures introduced the previous year continued. The parade route, which started at Queen’s Park, was curtailed at University and Wellington instead of proceeding to a drink-fueled party at the LCBO parking lot off Queen’s Quay. At the annual picnic on Olympic Island, where police were pelted with beer cans and bottles in 1985, suds were only available before 7:30 p.m. in the official beer garden and in plastic cups. Still, unless revellers were truly obnoxious, police tended to overlook open drinking on parade day.

The parade itself was a record-setter. After drawing 275,000 people the year before, organizers predicted 500,000 would show up in 1987. Their guess was correct: The crowds were so thick, especially south of Dundas Street, that police and parade marshals urged spectators to stand back so that the 26-band procession could move. Police gave up maintaining the steel barriers dividing the procession from onlookers, especially since the crowd was well-behaved. As staff-superintendent Dave Cowen observed, “We’ve had less problems here than at a Blue Jays game.” Attendees were impressed by the eight-hour spectacle: “It’s absolutely glorious,” noted 73-year old Downsview resident Goldie Caesar. “It just jiggled you out of your skin it was so invigorating.” Retired life-insurance broker Jack Stern told the Star that “you could be half-dead and once this music gets in your blood then you’re alive again.”

|

| Toronto Star, August 1, 1987. Click on image for larger version. |

While such costumes were meant to be enjoyed outdoors, their bulk was problematic during events held inside Varsity Arena. “Inside, it’s hot and stuffy with all the body heat,” 12-year-old Camille Noel told the Star during the Junior Carnival. While she endured the heat and humidity when dressed as a snowflake (complete with leotard, fake fur, and heavy plastic), others fainted or suffered headaches. One person who kept cool was Ontario Premier David Peterson, who was provided with industrial-strength fans while attending the King and Queen of the Bands contest. In between playing coy with the media over an impending election call, Peterson told the audience in the arena that “I’ve been to Trinidad and Caribana is better here than it is there!”

Organizers admitted that, with maturity, Caribana might have lost some of its funky, spontaneous spirit. The problem was finding ways to keep that spirit while addressing growing pains. “There’s still a carnival atmosphere,” Cox told the Star, “but we realize now that it has to be managed properly.” One vow organizers made was to keep the parade free of charge to attendees—while an admission fee had once been discussed, it was determined the potential revenue stream would violate the festival’s tradition of openness. Caribana “has to be open in the streets and everyone has to participate in it,” observed lawyer Charles Roach, one of the festival’s founders in 1967. “It cannot be put in any kind of venue. That would go against a basic philosophy of the carnival spirit. Caribana is about freedom.”

Additional material from the August 3, 1987 edition of the Globe and Mail, the July 23-29, 1987 edition of Now, and the July 27, 1987, July 31, 1987, August 1, 1987, and August 2, 1987 editions of the Toronto Star.

Comments