This installment of my "Ghost City" column for The Grid was originally published on December 4, 2012. A longer story about Hans Fread later appeared as a Historicist column for Torontoist.

|

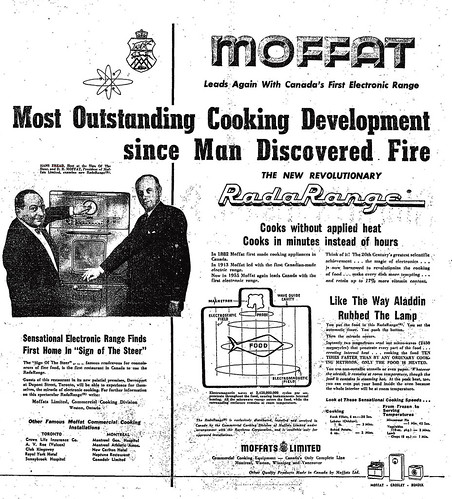

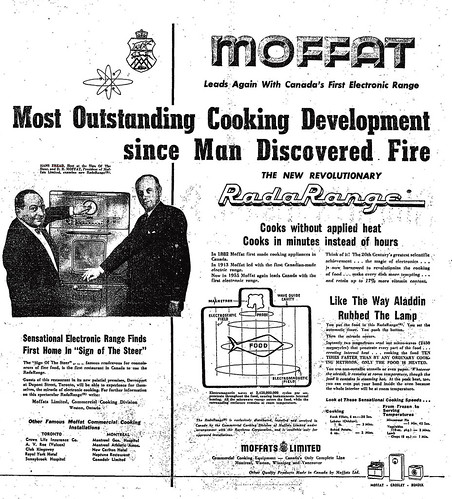

| Sign of the Steer restaurant, northeast corner of Davenport and Dupont, 1955. City of Toronto Archives, Fonds 1257, Series 1057, Item 504. Click on image for larger version. |

Food and furnishings. These have been the staples for the revolving door of occupants at the northeast corner of Davenport Road and Dupont Street for over half-a-century.

Back at the turn of the 1960s, this high-turnover site brought such ruin to original owner Hans Fread, Canada’s first star chef, that 146 Dupont was known for years as “Hans Fread’s Folly.” However, for this notoriously outspoken restaurateur, most of his follies were self-inflicted; as he once admitted, “I am sometimes like a little boy with a big mouth—when I am angry, I talk too much and it comes back to hurt me.” Originally a lawyer in Germany, Fread fled to Canada in 1934 to escape the Nazi regime he openly criticized. Arriving in Toronto during World War II, he worked at the King Edward Hotel before opening Sign of the Steer in a converted house at Dupont and St. George in 1948. Fread quickly attracted lineups for specialties like pan-fried steaks branded with a poker to resemble grill marks, and other European-styled meals that stood out in a dull dining town. And his word was the law during his meals—minor requests from diners for adjustments weren’t tolerated. His notoriety grew to the point that CBC offered him airtime on its new television service, which led to

Hans in the Kitchen (1953–54).

|

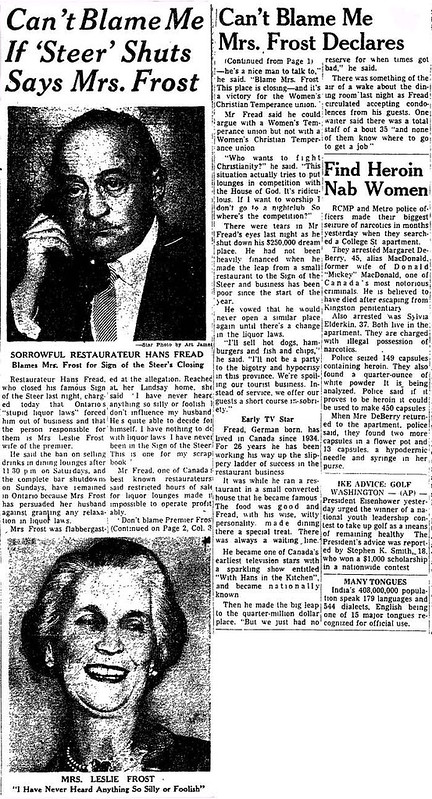

| Toronto Star, November 24, 1955. Click on image for larger version. |

Fread soon dreamt of a larger restaurant. He spent $250,000 to build a two-storey, 600-seat eatery at 146 Dupont. Mayor Nathan Phillips was among the speakers when the new Sign of the Steer stuffed its VIP guests silly during its opening meal in November 1955. Business was good during its first two years, during which Fread launched another cooking show on Hamilton’s CHCH.

|

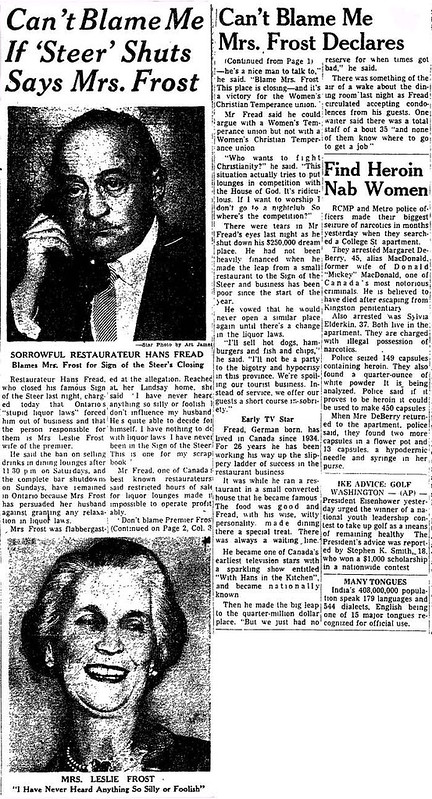

| Toronto Star, June 29, 1960. Click on image for larger version. |

However, the restaurant’s size and awkward car access, not to mention smarter competitors, eventually did Fread in. When Sign of the Steer closed in June 1960, Fread raged against Ontario’s antiquated liquor laws, which prevented him from serving drinks after 11:30 p.m. on Saturdays and not at all on Sundays. He specifically blamed the Women’s Christian Temperance Union and Premier Leslie Frost’s wife Gertrude for his woes. Mrs. Frost thought Fread’s charges were ridiculous—she had never eaten at his restaurant and claimed little influence on the premier’s liquor policy. “This is one for my scrapbook,” she noted.

Fread fled to Winnipeg, where he accused Torontonians of suffering “an inferiority complex” that made them “think a candle on the table makes good atmosphere.” Fread’s namecalling—he painted Toronto diners as “a multitude of Lady Plushbottoms”—was viewed by former competitors as sour grapes from somebody who overpriced his meals. “Time had passed him by,” steak-house proprietor Harry Barberian reflected years later, “but he didn’t realize it and blamed the world.” Despite his venom, Fread was back in Toronto within two years. Before his death in 1971, he cooked at or operated several restaurants and taught at George Brown College.

The next occupant of 146 Dupont was Winco, who owned the Steak n’ Burger chain. Their approach in the early 1960s was, according to spokesman Tony Mili, “to provide a middle-class man with high-class dining.” The site later became an Italian eatery, Peppio’s, which catered to “the guy with five bucks in his pocket who wants to take his girl out for dinner.” The concept lasted for a decade, though ads indicate numerous short-lived attempts to turn the upper level into a swinging hangout for groovy kids. An ad warned potential partiers that due to low prices, “you’ll have to bring your own go-go girls.”

|

| Toronto Star, November 1, 1975. Click on image for larger version. |

After a short stint as part of Winco’s Rib o’ Beef chain, Mili returned to an Italian theme as Anthony’s Villa. Opening in November 1975, the restaurant put unemployed musical-revue performers through a two-week rehearsal process to prepare them for their role as singing servers. The upper floor was converted into a cabaret that launched with an ode to clowns. Despite Mili’s dreams, a national chain based on the concept failed to materialize, and the curtain fell on Anthony’s after two years. The site housed a ballroom-dancing venue and a few more restaurants, including a branch of Giustini, a Montreal-based topless steakhouse chain.

|

| Toronto Star, August 10, 1978. |

By the 1990s, the culinary gods gave up on the building. A succession of mostly high-end home décor and furniture businesses followed, ranging from interior decorators to rug dealers. For several years, 146 Dupont became the W Lounge, touted as a hidden spot to stargaze during the Toronto International Film Festival. Currently, the building is home to D.O.T. Furniture and a presentation office for the O2 Maisonettes on George project, whose make-upped mascot might just be a leftover clown from Anthony’s.

Additional material from the November 23, 1955, October 28, 1964, and September 16, 1970 editions of the Globe and Mail, the June 29, 1960, October 17, 1960, October 19, 1960, November 24, 1962, February 28, 1964, and November 1, 1975 editions of the Toronto Star, and the June 1996 edition of Toronto Life.

Comments