the smiling men of pasadena 2: the eternal smile of "uncle bill" haas

From the accounts I've found, it seems William A. Haas was a classic old-time entertainment PR man, full of stories and tall tales to go along with his eternal smile. When he died in 1941, his obituary included many claims that might not hold up under scrutiny.

- He unsuccessfully ran for coroner (possibly in Iowa) against future president William Howard Taft.

- He suggested that William McKinley be promoted as the “Advance Agent of Prosperity” during the 1896 presidential campaign.

- He planted the idea of motion pictures in Thomas Edison’s head.

- Around 1914, he presented the first movie preview.

More believable was his hiring of a teenage violinist while working at a theatre in Waukegan, Illinois around 1910. The budding musician grew up to be comedian Jack Benny, who sent Haas birthday greetings in later years.

Born in Illinois, Haas’s career began on the vaudeville circuit at the end of the 19th century. He served as road manager for the infamous Cherry Sisters, five siblings whose questionable talents drew vegetable-tossing crowds across the country. In the late 1920s he unsuccessfully attempted to raise interest in producing a biopic about the sisters, whose awareness of how bad they were remains debatable.

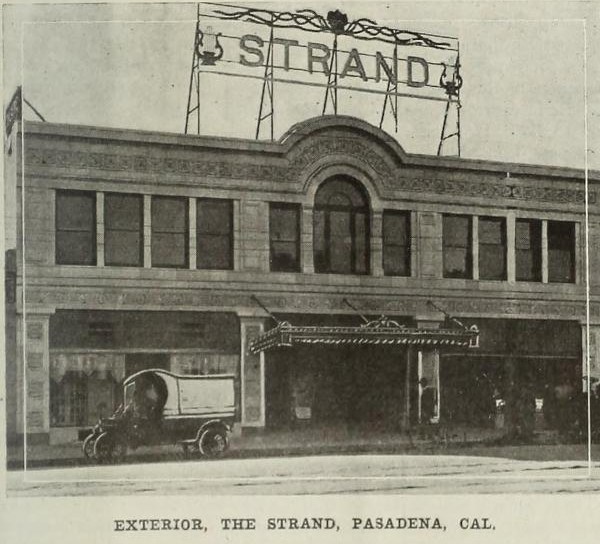

Strand Theatre, Pasadena. Uploaded by elmorovivo on Cinema Treasures. Creative Commons.

Haas moved to Pasadena in 1914 to open the Strand Theatre. After an ownership change, Haas briefly moved over to the Raymond Theatre, then, still smiling, he returned to the Strand as manager in 1921. “With the good nature that always is characteristic of Mr. Haas the smile on his face has become more intense,” the Pasadena Post reported. “You will find him at the door, always ready with a hand grasp, always a pleasant word, always a smile.”

Exhibitors Herald, February 11, 1922.

In February 1922 Haas was charged with violating Pasadena’s censorship ordinance by showing a comedy that had not been reviewed by the censors. His arrest followed that of the manager of the Raymond for continuing to show Cecil B. DeMille’s The Affairs of Anatol after censors gave it a thumbs down. When pioneering western star William S. Hart’s film Travelin’ On was banned, Haas asked Hart to come to Pasadena to talk about censorship. “What’s the use?” Hart responded. “I won’t waste time on talk now. What is required is action.” Rumours spread that Hart and Paramount executive Jesse L. Lasky considered suing the City of Pasadena for $100,000, but, as far as I can tell, no suit was filed. A decade later Haas applied to be the city’s chief movie censor.

Pasadena Post, October 13, 1921.

Haas resigned from the Strand soon after, quickly resurfacing as manager of the Ambassador Theatre in Los Angeles. He quickly ran into controversy when an injunction was threatened in January 1923 against the preview showing of the anti-drug drama The Greatest Menace by author/philanthropist Angela Kaufman. Haas told the Los Angeles Times that Kaufman’s letter indicated the movie failed to follow her scenario and was poorly assembled. Attorneys for the film’s cast successfully defeated a restraining order and the preview went ahead.

Sidebar: The film’s troubles were far from over: within days, producer James Calnay was charged with assault for kicking Kaufman in the stomach after an argument over the film. Both parties blamed the other for the film’s problems, and each claimed ownership of the picture. Calnay was also charged with passing bad cheques to Kaufman. When the assault case went to court, Kaufman blamed the incident on Calnay’s temper. Calnay pleaded self-defense, fearing she was about to attack him. He claimed the argument stemmed from a disagreement over how long it took someone to become a narcotic addict—Kaufman insisted three weeks, Calnay believed it took longer. Calnay eventually sold his interest in the film to Kaufman, and spent the rest of 1923 in and out of court over failure to pay wages for several film projects.

Pasadena Post, August 18, 1941.

Next: Cigars and Preserves

Sources: the June 27, 1921, February 25, 1922, March 29, 1922, August 1, 1929, September 13, 1933, and August 18, 1941 editions of the Pasadena Post; and the March 30, 1922, January 21, 1923, January 22, 1923, January 24, 1923, January 25, 1923, March 11, 1923, March 27, 1923, and September 6, 1923 editions of the Los Angeles Times.

Comments