watching from windsor '67 part one: unrest breaks out

|

| Poster hanging outside the Detroit Historical Museum, July 8, 2017. |

A police raid on a “blind pig” (an unlicensed drinking

venue) at 12th Street and Clairmount Avenue in the early morning

hours of July 23, 1967 provided the fuse for five days of civil unrest in

Detroit. Whether you call what happened that week a rebellion, riot, or

uprising, the repercussions are still evident around the city, and remain a

well-debated subject.

Given Detroit’s proximity to Canada, the events that

unfolded affected Windsor, and were commented on elsewhere around the country.

What I aim to do with these posts is show Canadian reaction to the events in Detroit,

primarily from newspapers in Toronto and Windsor.

This series grew from several streams of things I’ve done

over the past year:

- Collecting newspaper stories: Side stories I saved while researching Canada’s centennial, others I tracked down out of personal interest.

- Museum visits: if you’re visiting Detroit during the next two years, I highly recommend the Detroit Historical Museum’s Detroit 67:Perspectives exhibit, and its accompanying online material.

Some of this material was originally gathered for a piece I

was going to write for an online publication, but was abandoned due to other

commitments and finding many side stories about race in Essex County during the

1960s. These stories I want to explore further, and will write about as time

permits. I’m still digesting some of these events around Amherstburg and Harrow,

stories never discussed during my formative years which are eye-opening (but

not terribly shocking).

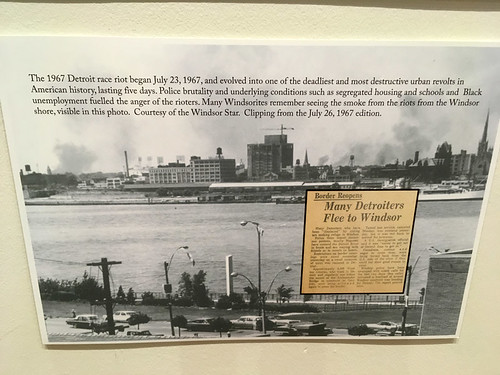

|

| Part of an exhibit on 1967 in Windsor on display at the Chimczuk Museum. Photo taken July 9, 2017. |

In his book Turning Points: The Detroit Riot of 1967, A

Canadian Perspective, Herb Colling describes the atmosphere in Windsor as July

23 wore on.

For most people in Windsor, July 23 is a normal summer Sunday with church attendance, swim meets, backyard barbecues and picnics in the park but, by afternoon, the reality of racial turmoil is literally burned into the Canadian consciousness. At 2:00 p.m., the first smudges of black smoke in Detroit are visible from Windsor. As darkness falls, five major fires burn several blocks apart; their flames reflect orange and pink off the clouds.

All afternoon, Windsorites congregate in waterfront parks on the border to watch the smoke and listen for sounds of the riot. Teenage boys sit on the hoods of their cars or lean against break walls as they hug their girlfriends protectively. They gossip with picnickers and fishermen, point and exclaim every time they see a new disturbance. In Canada, the riot is a uniting force, a powerful draw for a shocked people with a morbid fascination—a horror on one hand and yet an excitement that something significant is happening in their own backyard.

Curiosity over what was going on created traffic jams along

Riverside Drive. “Most of the time [the fires] appeared as dull, rosy glows

against the skyline,” the Windsor Star reported, “but every now and then a

tongue of flame shot into the air in a spectacular burst visible for miles” A

band concert scheduled for Dieppe Gardens that evening went ahead, with the

smoke providing a backdrop. Reading the descriptions feels like there was an element of spectator sport going on among those who gathered on the waterfront, with the mix of awe and horror that accompanies watching crashes.

There was a limit to how much Windsorites could fulfill

their curiosity. By 9 p.m. the border was closed except for emergency personnel

and those who could prove they had legitimate business or pre-scheduled

vacations allowed to cross into the United States. Tunnel bus service was

suspended. Chrysler workers were sent home when parts were held up in Detroit.

People were stuck on either side of the border, resulting in nights spent with

friends and relatives, jammed phone lines, and hotels on the outskirts of

Windsor filled to capacity. Some Detroiters jumped in their boats and sailed

over to Canada.

|

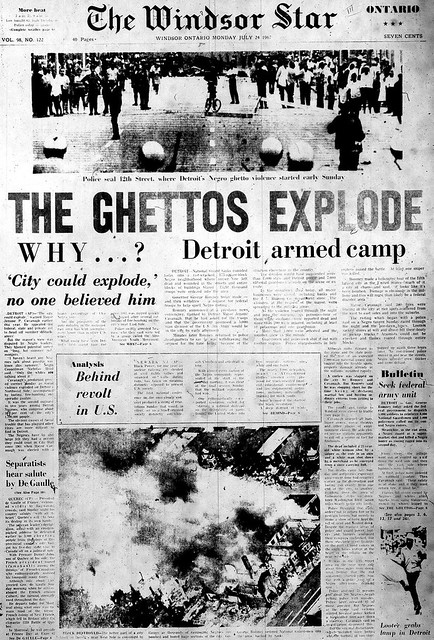

| Front page, Windsor Star, July 24, 1967. Click on image for larger version. |

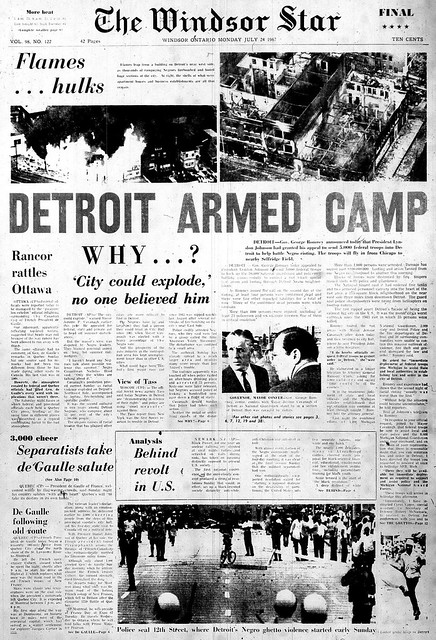

|

| Front page of final edition, Windsor Star, July 24, 1967. Click on image for larger version. |

While there was radio and television coverage, newspaper

readers in Windsor and elsewhere in Canada had to wait until the morning

editions rolled off the presses on July 24 for print analysis.

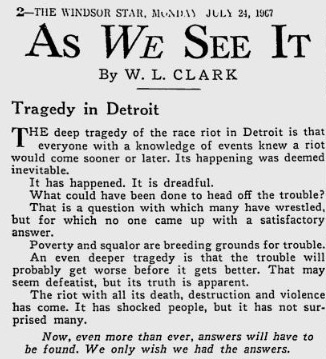

Columnist John Lindblad expresses the ill-feelings and unease conventional media had toward growing black militancy of the era:

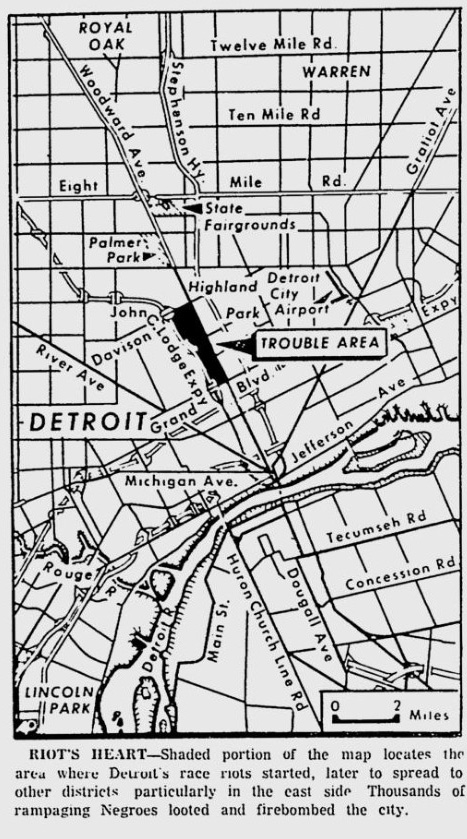

There were maps of where the unrest was occuring:

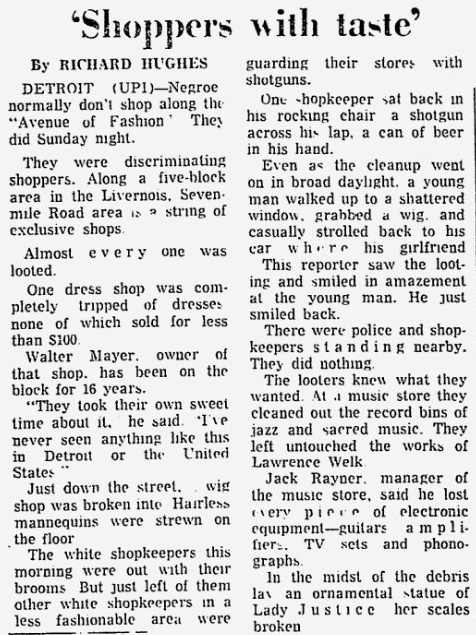

And there stories such as this one, about looters clearing out stores along the "Avenue of Fashion" along Livernois. Apparently Lawrence Welk albums were not a hot commodity.

Starting that afternoon, coverage of the unrest in Detroit competed for front page space in Canadian papers with the fallout from another story unfolding on July 24: French president Charles de Gaulle’s “Vive le Quebeclibre!” speech in Montreal.

And there stories such as this one, about looters clearing out stores along the "Avenue of Fashion" along Livernois. Apparently Lawrence Welk albums were not a hot commodity.

Starting that afternoon, coverage of the unrest in Detroit competed for front page space in Canadian papers with the fallout from another story unfolding on July 24: French president Charles de Gaulle’s “Vive le Quebeclibre!” speech in Montreal.

Let’s just say there’s lot of anger toward deGaulle and his words on editorial pages as the week goes on...

|

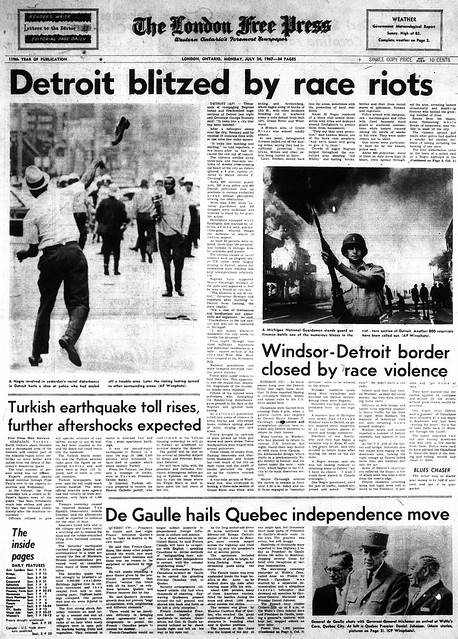

| Front page, London Free Press, July 24, 1967. Click on image for larger version. |

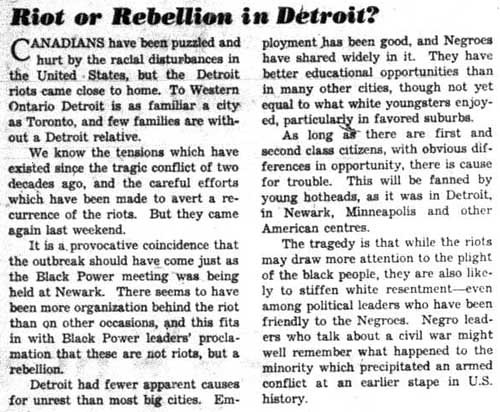

The London Free Press’s evening edition raised the question

of whether a riot or rebellion was happening:

|

Apart from straight reporting, there was little commentary

in Toronto’s papers on July 24. Here are the front pages from each of the city's three dailies.

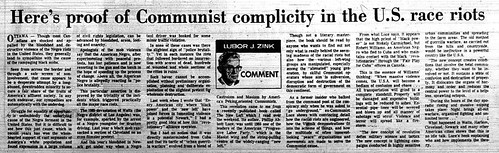

The closest piece to editorial comment that day was Lubor Zink’s column in the Telegram, which I suspect was in the can before unrest broke out in Detroit. Commenting on black riots throughout the United States in recent years, the eternal Red-fighter naturally detected “Communist complicity” in what was going down.

|

| Front page, Globe and Mail, July 24, 1967. Click on image for larger version. |

|

| Front page, Toronto Star, July 24, 1967. Click on image for larger version. |

|

| Front page, Telegram, July 24, 1967. Click on image for larger version. |

The closest piece to editorial comment that day was Lubor Zink’s column in the Telegram, which I suspect was in the can before unrest broke out in Detroit. Commenting on black riots throughout the United States in recent years, the eternal Red-fighter naturally detected “Communist complicity” in what was going down.

|

| Click on image for larger version. |

Next: Coverage from July 25, 1967.

Comments