off the grid: ghost city the bayview ghost

This installment of my "Ghost City" column for The Grid was originally published on January 8, 2013.

When East York rejected physician Charles Trow’s offer to sell his 25-acre wooded property south of Leaside to the municipality for use as parkland circa 1950, little did political officials realize the headaches that would ensue over the next half-century.

Instead, the property—which offered a beautiful view of the Don Valley—was sold by Trow’s widow in 1953 to developers Hampton Park Company Ltd. Legal problems arose almost immediately as Hampton Park proprietors Harry Freedman and Harry Frimerman beat a foreclosure attempt when they were slow to pay the mortgage. The site was approved for apartment development in East York’s first official plan in 1957, but the document was scrapped when the township planner was fired for consulting with tower builders on the side.

As Hampton Park developed its plans for the site, residents in the adjoining Governor’s Bridge neighbourhood were alarmed by the prospect of a flood of new neighbours and a reduced view of the Don Valley. Lobbying by the Governor’s Bridge Ratepayers Association (GBRA) resulted in an East York bylaw prohibiting the clearing of more than one acre of land. Hampton Park found a loophole by subdividing the property among family members into lots of less than an acre each. East York reeve Jack Allen shocked everyone by approving, without provisions for servicing the site with sewage and water, a building permit in October 1959 for two 105-unit buildings near the recently completed Bayview Avenue extension. Hampton Park worked day and night to erect their white-coloured apartment complex as the shock set in.

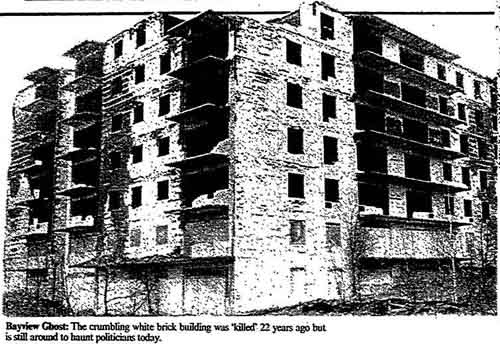

While Allen later claimed the builders had every legal right to proceed, East York council moved quickly to halt the project. When the building permit was revoked on November 9, 1959, the structure was a seven-storey shell that had a roof but lacked doors, elevators, and windows. Spurred by new reeve True Davidson, East York attempted to rezone the site as parkland, but Hampton Park dug in its heels. A fiery session of Metro Toronto council in May 1961 saw Davidson attack Metro Toronto chairman Frederick Gardiner because his law firm worked for Hampton Park. The GBRA repeatedly called for a judicial inquiry into the property. The issue went to the Ontario Municipal Board (OMB) in September 1961 but, frustrated by the conflicting accounts of the site’s saga, reserved any decision until matters were settled at the Ontario Court of Appeal. The wait lasted two decades.

The shell earned the nickname “Bayview Ghost” for its white appearance and decaying state. It served, the Star observed in 1966, as “a haven for wine drinkers and juvenile delinquents.” Depending on one’s point of view, it was a Don Valley landmark or an eyesore waiting for a tragedy. In 1969, the Labourers Union campaigned to tear it down after safety director Norbert Pike toured the site. His verdict: “a chamber of horrors” with infinite construction safety violations. “If nobody has been killed in here,” Pike told the Star, “it’s a bloody miracle.” Despite Pike’s efforts, local officials passed to buck as to who held the authority to knock the Ghost down.

The 1970s saw a battle of wills between East York and the increasingly elusive site owners. The property was on the verge of being seized for back taxes when Hampton Park paid its bill. Under the guise of Ranch Home Builders, the owners pushed an 880-unit project, which was the final straw for East York council. The municipality convinced the provincial government to pass special legislation in 1979 that granted East York the power to demolish any building in “a ruinous or dilapidated state” that had gone unoccupied for three years. Hampton Park applied for a judicial review, claiming East York abused its power by attempting to claim the property without satisfactory compensation.

When the battle finally returned to the OMB, nearby residents testified that the new project would destroy the close-knit nature of their neighbourhoods, a stance a Star editorial felt held “more sentimental nostalgia than good sense.” The paper laughed at claims that the new residences would be a “visual calamity,” given the state of the Bayview Ghost. In its November 1980 decision, the OMB approved the project at half its intended size. East York Mayor Alan Redway found the decision “completely unacceptable” and appealed to the provincial cabinet to overturn it. The province agreed with East York’s density arguments and tossed out the OMB decision in March 1981. Redway couldn’t disguise his glee to the press—“This is it. After 22 years, this is really it.” Two months later, the courts upheld the 1979 demolition legislation, but ordered East York to cover the demolition cost. A fundraising attempt to cover the estimated $250,000 required to knock the Ghost down by selling bricks for a dollar only raised $300 over a three-and-a-half month period.

The fate of the building was sealed in September 1981 when Hampton Park consented to fund the demolition. The company signed an agreement with East York to knock the structure down by year end, mix the rubble into the ground, top it with dirt to allow grass to grow, and complete and service a 66-home development within two years. Redway was at the controls when a wrecking ball painted like a Jack O’Lantern took its first swing at the building amid a party-like atmosphere on October 30, 1981. Looking on grumpily was part-owner Morris Freedman, who told the Star, “This shouldn’t have been demolished. People should have been living here 22 years ago. But it’s a democracy. People get what they want.” Some bricks, along with other artifacts, wound up in a display at Todmorden Mills.

Thanks to further legal disputes, the homes weren’t built for another two decades. Developers unconnected with Hampton Park finally pushed ahead with the Governor’s Bridge Estates at the dawn of the 21st-century. The Bayview Ghost continues to haunt the site: The only street leading off True Davidson Drive is called Hampton Park Crescent.

Additional material from Leaside, Jane Pitfield, editor (Toronto: Natural Heritage, 2000); the June 10, 1961, May 1, 1979, January 26, 1980, September 15, 1981, and October 31, 1981 editions of the Globe and Mail, and the September 29, 1961, December 2, 1966, August 25, 1969, May 10, 1980, May 15, 1980, November 21, 1980, March 17, 1981, and May 16, 1981 editions of the Toronto Star.

|

| Toronto Star, March 22, 1981. |

When East York rejected physician Charles Trow’s offer to sell his 25-acre wooded property south of Leaside to the municipality for use as parkland circa 1950, little did political officials realize the headaches that would ensue over the next half-century.

Instead, the property—which offered a beautiful view of the Don Valley—was sold by Trow’s widow in 1953 to developers Hampton Park Company Ltd. Legal problems arose almost immediately as Hampton Park proprietors Harry Freedman and Harry Frimerman beat a foreclosure attempt when they were slow to pay the mortgage. The site was approved for apartment development in East York’s first official plan in 1957, but the document was scrapped when the township planner was fired for consulting with tower builders on the side.

As Hampton Park developed its plans for the site, residents in the adjoining Governor’s Bridge neighbourhood were alarmed by the prospect of a flood of new neighbours and a reduced view of the Don Valley. Lobbying by the Governor’s Bridge Ratepayers Association (GBRA) resulted in an East York bylaw prohibiting the clearing of more than one acre of land. Hampton Park found a loophole by subdividing the property among family members into lots of less than an acre each. East York reeve Jack Allen shocked everyone by approving, without provisions for servicing the site with sewage and water, a building permit in October 1959 for two 105-unit buildings near the recently completed Bayview Avenue extension. Hampton Park worked day and night to erect their white-coloured apartment complex as the shock set in.

|

| Toronto Star, June 13 1961. |

While Allen later claimed the builders had every legal right to proceed, East York council moved quickly to halt the project. When the building permit was revoked on November 9, 1959, the structure was a seven-storey shell that had a roof but lacked doors, elevators, and windows. Spurred by new reeve True Davidson, East York attempted to rezone the site as parkland, but Hampton Park dug in its heels. A fiery session of Metro Toronto council in May 1961 saw Davidson attack Metro Toronto chairman Frederick Gardiner because his law firm worked for Hampton Park. The GBRA repeatedly called for a judicial inquiry into the property. The issue went to the Ontario Municipal Board (OMB) in September 1961 but, frustrated by the conflicting accounts of the site’s saga, reserved any decision until matters were settled at the Ontario Court of Appeal. The wait lasted two decades.

The shell earned the nickname “Bayview Ghost” for its white appearance and decaying state. It served, the Star observed in 1966, as “a haven for wine drinkers and juvenile delinquents.” Depending on one’s point of view, it was a Don Valley landmark or an eyesore waiting for a tragedy. In 1969, the Labourers Union campaigned to tear it down after safety director Norbert Pike toured the site. His verdict: “a chamber of horrors” with infinite construction safety violations. “If nobody has been killed in here,” Pike told the Star, “it’s a bloody miracle.” Despite Pike’s efforts, local officials passed to buck as to who held the authority to knock the Ghost down.

|

| Toronto Star, August 25, 1969. |

The 1970s saw a battle of wills between East York and the increasingly elusive site owners. The property was on the verge of being seized for back taxes when Hampton Park paid its bill. Under the guise of Ranch Home Builders, the owners pushed an 880-unit project, which was the final straw for East York council. The municipality convinced the provincial government to pass special legislation in 1979 that granted East York the power to demolish any building in “a ruinous or dilapidated state” that had gone unoccupied for three years. Hampton Park applied for a judicial review, claiming East York abused its power by attempting to claim the property without satisfactory compensation.

|

| Toronto Star, June 3, 1975. |

When the battle finally returned to the OMB, nearby residents testified that the new project would destroy the close-knit nature of their neighbourhoods, a stance a Star editorial felt held “more sentimental nostalgia than good sense.” The paper laughed at claims that the new residences would be a “visual calamity,” given the state of the Bayview Ghost. In its November 1980 decision, the OMB approved the project at half its intended size. East York Mayor Alan Redway found the decision “completely unacceptable” and appealed to the provincial cabinet to overturn it. The province agreed with East York’s density arguments and tossed out the OMB decision in March 1981. Redway couldn’t disguise his glee to the press—“This is it. After 22 years, this is really it.” Two months later, the courts upheld the 1979 demolition legislation, but ordered East York to cover the demolition cost. A fundraising attempt to cover the estimated $250,000 required to knock the Ghost down by selling bricks for a dollar only raised $300 over a three-and-a-half month period.

|

| Toronto Star, October 31, 1981. |

The fate of the building was sealed in September 1981 when Hampton Park consented to fund the demolition. The company signed an agreement with East York to knock the structure down by year end, mix the rubble into the ground, top it with dirt to allow grass to grow, and complete and service a 66-home development within two years. Redway was at the controls when a wrecking ball painted like a Jack O’Lantern took its first swing at the building amid a party-like atmosphere on October 30, 1981. Looking on grumpily was part-owner Morris Freedman, who told the Star, “This shouldn’t have been demolished. People should have been living here 22 years ago. But it’s a democracy. People get what they want.” Some bricks, along with other artifacts, wound up in a display at Todmorden Mills.

Thanks to further legal disputes, the homes weren’t built for another two decades. Developers unconnected with Hampton Park finally pushed ahead with the Governor’s Bridge Estates at the dawn of the 21st-century. The Bayview Ghost continues to haunt the site: The only street leading off True Davidson Drive is called Hampton Park Crescent.

Additional material from Leaside, Jane Pitfield, editor (Toronto: Natural Heritage, 2000); the June 10, 1961, May 1, 1979, January 26, 1980, September 15, 1981, and October 31, 1981 editions of the Globe and Mail, and the September 29, 1961, December 2, 1966, August 25, 1969, May 10, 1980, May 15, 1980, November 21, 1980, March 17, 1981, and May 16, 1981 editions of the Toronto Star.

Comments