off the grid: ghost city 660 broadview avenue (william peyton hubbard)

This installment of my "Ghost City" column for The Grid was originally published on February 12, 2013.

When William Peyton Hubbard was born in 1842 it’s doubtful his father, a freed slave who had arrived in Toronto two years earlier, imagined that the infant would become one of the city’s most powerful politicians. The road to that accomplishment took time: Before Hubbard entered politics in 1893, he baked cakes and drove a horse cab, occupations that were the norm for the city’s small black population.

While on his rounds one night, Hubbard noticed another cab about to fall into the Don River. He picked up its occupant, who turned out to be George Brown. The Globe publisher hired Hubbard as his personal driver and encouraged him to enter the political realm. Brown was long in the grave by the time Hubbard made his first run for office in Ward 4, which stretched between Bathurst Street and Avenue Road. Though Hubbard lost his first attempt, he was elected as Toronto’s first black alderman in 1894 and remained at City Hall until 1908.

Nicknamed “the Cicero of the Council,” Hubbard was one of its best prepared, most critical members. “His brutal honesty and penchant for publicly assailing colleagues he felt were in the wrong often led him to the brink of slander,” his biographer and great-great-grandson Stephen Hubbard observed. “He only staved off court appearances because of his meticulous study of issues.” Getting to the heart of a matter was most important to him, regardless of the means he used. An undated clipping in his personal scrapbook noted that “he shows great wisdom in dealing with matters affecting wards other than No. 4.”

He earned a reputation as a municipal reformer with an eye on the financial bottom line. Hubbard promoted projects ranging from public management of water to making city government more democratic. He led the call to have the Board of Control, which served as the mayor’s executive committee, elected by the public instead of council. During the first open Board of Control election in 1904, not only did Hubbard become the first visible minority elected by the city at large, he also earned the highest vote tally. Besides acting as the board’s vice-chairman, he occasionally served as acting mayor and represented the city at various municipal associations.

Scanning old newspaper clippings reveals a refreshing lack of references to his race. Partly it was due to Hubbard rarely ever making an issue of it. Though racism was a reality for blacks in Toronto during Hubbard’s lifetime, the respect he earned for his talents outweighed the few open attacks on his skin colour. Mostly, it appears Hubbard and the press enjoyed a mutually satisfying relationship—the papers liked his direct, forceful speaking style and underdog leanings. “I have a big place in my heart for the newspaper boys,” he told the Star in 1927.

While Hubbard’s advocacy for public ownership of the electrical system was successful, it cost him at the ballot box in 1908 when many of his pro-privatization supporters turned against him. After his defeat, he moved from Ward 4 to 660 Broadview Avenue. He wasn’t the only family member to settle into the row of Edwardian homes south of Danforth Avenue—his son Frederick, who later served as a TTC commissioner, lived next door.

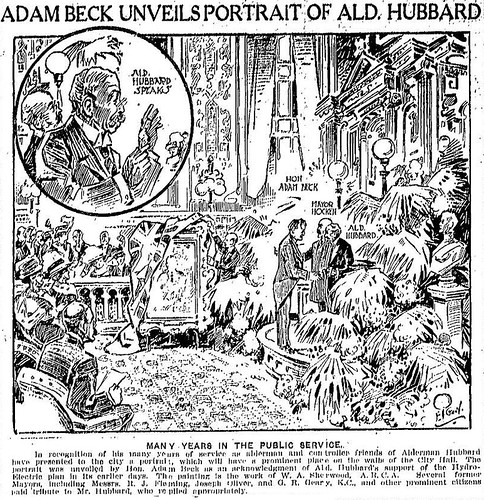

Hubbard briefly returned to city council in 1913 but retired when his wife fell ill. He was honoured for his long civic service that November with a ceremonial unveiling of a portrait (seen above) that still graces a City Hall committee room. He remained active as a member of various boards, including a 40-year association with the House of Industry social services agency.

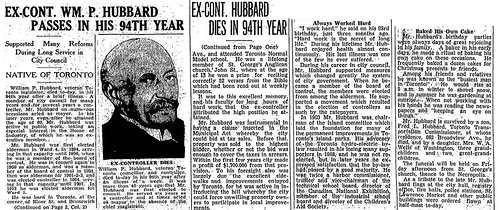

As he aged, the press provided birthday updates, noting his mind was still sharp and he used his early baking skills to make his own celebration cakes. When Hubbard died at age 93 in April 1935, flags at municipal buildings flew at half-mast.

His home soon passed into other hands, and was used as a private residence and offices for medical professionals until it became a rooming house during the 1960s. Montcrest School bought the property in 1995 and renovated it for classrooms. The building was renamed Hubbard House in 2008. The next year, a plaque honouring Hubbard was placed out front. It replaced a damaged plaque that had sat in Riverdale Park for 30 years.

Additional material from William Peyton Hubbard’s personal scrapbooks at the City of Toronto Archives, Against All Odds by Stephen L. Hubbard (Toronto: Dundurn, 1987), and the January 27, 1927 and April 30, 1935 editions of the Toronto Star.

This article also spawned the following bonus features, published on this site on February 13, 2013.

|

| Portrait of William Peyton Hubbard, 1913, by W.A. Sherwood. |

While on his rounds one night, Hubbard noticed another cab about to fall into the Don River. He picked up its occupant, who turned out to be George Brown. The Globe publisher hired Hubbard as his personal driver and encouraged him to enter the political realm. Brown was long in the grave by the time Hubbard made his first run for office in Ward 4, which stretched between Bathurst Street and Avenue Road. Though Hubbard lost his first attempt, he was elected as Toronto’s first black alderman in 1894 and remained at City Hall until 1908.

|

| Editorial, the Globe, November 6, 1913. |

He earned a reputation as a municipal reformer with an eye on the financial bottom line. Hubbard promoted projects ranging from public management of water to making city government more democratic. He led the call to have the Board of Control, which served as the mayor’s executive committee, elected by the public instead of council. During the first open Board of Control election in 1904, not only did Hubbard become the first visible minority elected by the city at large, he also earned the highest vote tally. Besides acting as the board’s vice-chairman, he occasionally served as acting mayor and represented the city at various municipal associations.

|

| Photo of 660 Broadview Avenue as it appeared in the original article. |

While Hubbard’s advocacy for public ownership of the electrical system was successful, it cost him at the ballot box in 1908 when many of his pro-privatization supporters turned against him. After his defeat, he moved from Ward 4 to 660 Broadview Avenue. He wasn’t the only family member to settle into the row of Edwardian homes south of Danforth Avenue—his son Frederick, who later served as a TTC commissioner, lived next door.

|

| Toronto Star, November 6, 1913. Click on image for larger version. |

As he aged, the press provided birthday updates, noting his mind was still sharp and he used his early baking skills to make his own celebration cakes. When Hubbard died at age 93 in April 1935, flags at municipal buildings flew at half-mast.

|

| Toronto Star, April 30, 1935. Click on image for larger version. |

Additional material from William Peyton Hubbard’s personal scrapbooks at the City of Toronto Archives, Against All Odds by Stephen L. Hubbard (Toronto: Dundurn, 1987), and the January 27, 1927 and April 30, 1935 editions of the Toronto Star.

***

This article also spawned the following bonus features, published on this site on February 13, 2013.

Among the neat things I found while looking through the city archive files on William Peyton Hubbard was a letter from 1907 stamped with Toronto's official civic seal. The document was an official notice from Mayor Emerson Coatsworth vouching for Hubbard while the latter toured Washington and other American cities. Given the racial attitudes of the time, I suspect there were numerous occasions this letter aided Hubbard.

Mr. Hubbard is a highly esteemed citizen of Toronto. He is now and has been for many years a leading member of our City Council, during which time he has occupied a number of positions of prominence. He has been repeatedly elected to the Board of Control by the City at large, and has occupied the position of Vice-Chairman of the Board, a position second only in importance to that of Mayor of the City.Controller Hubbard’s keen interest in all municipal public works and services may lead him to seek information in the various cities visited by him, in which case we bespeak for him that kindly courtesy and consideration which we are sure the presentation of this letter will secure.

Other items Hubbard preserved from his trip include visitor passes to government buildings in Washington.

The unfortunate part of Hubbard’s preserved scrapbooks for researchers is that the sources for most clippings are not identified. Take this item: a cartoon commenting on Hubbard’s vote count during the 1906 municipal election. Besides the event depicted, one other element helps identify the timing and source right off the bat: the signature of “Rostap,” which was the pen name of Telegram cartoonist Owen Staples. Unfortunately, many of the other clippings have no such markers, which leads a researcher trying to source a piece down the road of identifying typefaces commonly used by a paper before hitting a microfilm machine.

Comments