This installment of my "Ghost City" column for The Grid was originally published on January 22, 2013.

|

| Toronto Star, October 26, 1948. |

Until 1948, anyone headed to the southwest corner of Bloor Street and Concord Avenue typically went to peruse the area’s long succession of furniture businesses, looking for that perfect addition to their home décor. The granting of a liquor license that year to the Concord Tavern ushered in the intersection’s long association with music as a venue and instrument seller.

During the Concord’s early days, food was pushed as much as booze or music. An early ad promised “epicurean delights from the continent prepared under the direction of Chef ‘Van’” to be devoured while pianist Leo Spellman tickled the ivories. The Concord offered four rooms for its patrons, with names that ranged from swanky (Burgundy Room) to vaguely sexy sounding (Frolic Room).

|

| Toronto Star, January 8, 1962. |

The tavern’s musical offerings evolved from lounge acts to rock ‘n’ roll. Talent booker Jack Fisher claimed that the venue helped break mid-1950s hitmakers like the

Crew Cuts and the

Four Lads.

Bo Diddley,

Duane Eddy, and

Conway Twitty were among the headliners during the early 1960s. But it was a Saturday matinee series launched in 1960 starring

Ronnie Hawkins which heavily influenced the local music scene. The bar was divided in two so that teens could enjoy performers they legally couldn’t see at night in a non-alcoholic setting. According to music historian

Nicholas Jennings, the matinees “drew budding musicians eager to study the stage moves and musical repertoire of what was then the city’s top professional band. The kids sat in the non-alcoholic section where, for the cost of a Coke and a plate of fries, they could watch their heroes.” While future local headliners like

Robbie Lane and

Domenic Troiano watched in the audience, fellow teens like Robbie Robertson played onstage with

Hawkins in the backing group which

would eventually evolve into The Band.

|

| Globe and Mail, February 25, 1963. |

Hawkins found long-term bliss at the Concord matinees. Wanda Nagurski first dropped in one Saturday in September 1960, partly to get back into the swing of life following the death of her father. Ronnie “had many girls after him all the time,” she later told Hawkins biographer Ian Wallis. “I suppose I was a little different. These ladies would come in with their long nails, all acting proper. I was used to fighting and carrying on with my brother and sister, and would just behave silly and rough house around. I never dreamt in a million years that we’d be getting married and everything.” Hawkins was still regularly playing the Concord when he and Wanda tied the knot in March 1962.

With the turn to rock came various eyebrow-raising attractions. While the early 1960s saw plenty of people doing the Twist, the middle part of the decade brought in go-go dancers. Yellow-boot clad performers brought, according to the

Globe and Mail’s Martin Knelman, “all the richness of gymnasium culture to modern interpretive dancing,” especially if they performed while suspended from the ceiling. By 1969, the

Star reported that the Concord “goes in for raunchy toplessness,” foreshadowing the venue’s final incarnation as a strip joint.

|

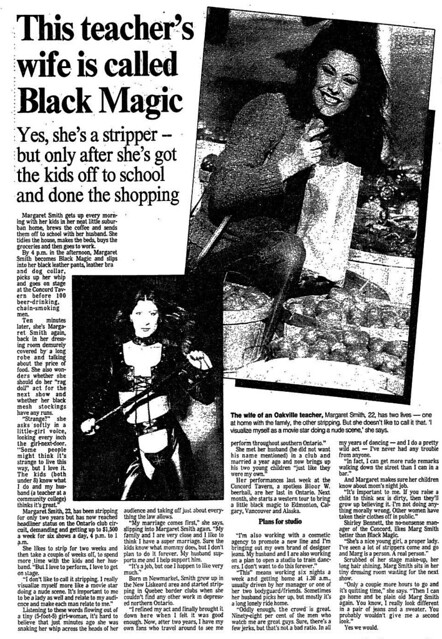

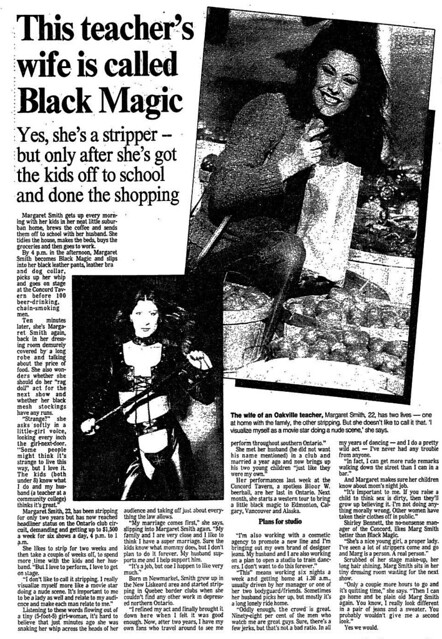

| Toronto Star, October 3, 1982. Click on image for larger version. |

During the late 1970s, the Concord offered three spaces: basement beer hall Grant’s Tomb, gambling-themed Black Jack’s Lounge, and a main-floor country music bar which was briefly one of the city’s top venues. Promoters who launched the “Stage West” series of nationally-known acts in 1979 hoped that the Concord would be to country what the recently shuttered Riverboat had been to raising the profile of folk music.

But it wasn’t to be. During its last years, the Concord morphed into a strip joint which attracted touring performers like Margaret Smith, a.k.a. Black Magic, who danced while attired in black leather and whips. What had once been a meeting place for locals and businessmen became a regular stop for 14 Division officers who stopped brawls between bikers in the parking lot, checked in on neighbourhood toughs, and even nabbed a drunk driver or two. Drug dealing and prostitution were not unknown.

|

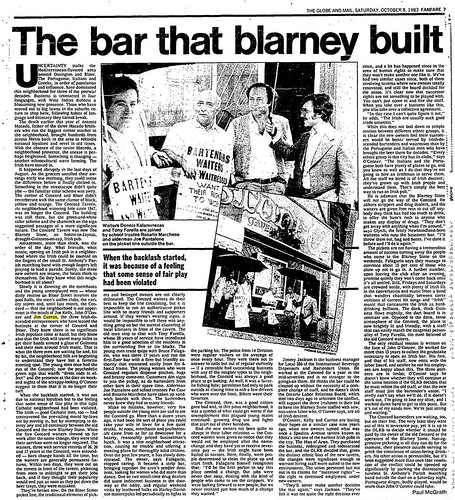

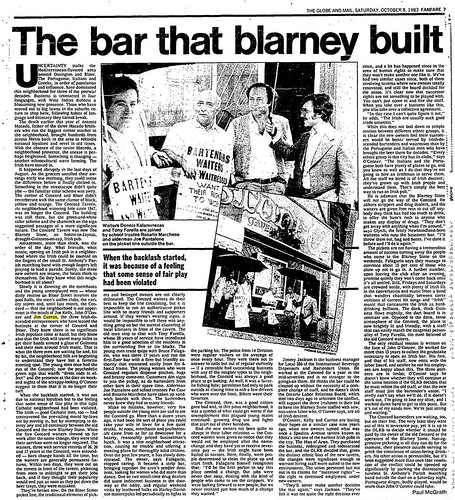

| Globe and Mail, October 8, 1983. Click on image for larger version. |

The star-spangled sign, once described as “pseudo-Mirvish Modern,” was removed in 1983 and replaced by a new name: the Blarney Stone. The Irish pub drew some neighbourhood ire when servers who had worked at the Concord for over 20 years were not retained. The new owners felt customers would be better served by bartenders and waitresses of Irish descent, rather than by the previous Italian and Portuguese servers. “I’d be the first person to say this place needed a change,” fired bartender Bruce Falagario told the

Globe and Mail. “Our jobs were never that easy, dealing with the kind of people who come to see the strippers. We were looking forward to new people, but we never realized just how much of a change they wanted.” The former employees picketed the new bar, with assistance from city councillor Joe Pantalone and school board trustee (and future MPP) Rosario Marchese.

After the Blarney Stone pumped its last pint around 1989, the space was taken over by its current tenant, Long & McQuade Musical Instruments.

Additional material from Before the Gold Rush by Nicholas Jennings (Toronto: Penguin, 1997), The Hawk: The Story of Ronnie Hawkins & the Hawks by Ian Wallis (Kingston: Quarry Press, 1996), the November 12, 1948, December 21, 1966, November 9, 1968, February 8, 1978, October 8, 1983 editions of the Globe and Mail, and the January 3, 1969 and October 3, 1982 editions of the Toronto Star.

Comments