off the grid: ghost city 696 yonge street

This installment of my "Ghost City" column for The Grid was originally published on January 29, 2013. The building is still boarded up as of this reprint.

The Church of Scientology’s Toronto headquarters are in the midst of an “Ideal Org” makeover—signalled, last month, by boards nailed to the Yonge Street high-rise. While it remains to be seen whether the move will fracture the controversial faith’s local followers as similar, costly refurbishings have in other cities, the plans are less than modest, indicating a colourful new façade will be placed on the almost-60-year-old office building, along with a new bookstore, café, theatre, and “testing centre” inside.

Built around 1955 in the International style of architecture, 696 Yonge’s initial tenant roster included recognizable brands like Avon cosmetics and Robin Hood flour. They were joined by an array of accounting firms, coal and mining companies, and the Belgian consulate, along with a number of construction and property management companies run by Samuel Diamond, whose name later graced the building.

By the 1970s, The Diamond companies were among the few original tenants remaining. Movie studio MGM settled in for a long stay, while the Ontario Humane Society teetered on the verge of financial ruin during its tenancy. There was a temporary office for a federal committee on sealing, which released a 1972 report recommending a temporary moratorium on seal hunting while solutions were sought to halt a population decline. The building even enjoyed a brief taste of religious controversies to come when the Unification Church—a.k.a. the “Moonies”—briefly opened an office, prompting questions about indoctrinated converts, growing wealth, and cult-like practices mirroring those later asked about the Church of Scientology.

L. Ron Hubbard’s religion, meanwhile, had shuffled around various sites in the city since the late 1950s, from meetings on Jarvis Street to a townhouse on Prince Arthur Avenue. The church’s reputation for defending itself grew as quickly as its membership—by the 1970s, official church statements were guaranteed to appear in the letters section within days of any faintly critical newspaper article. The Church of Scientology bought 696 Yonge in 1979.

Around 2:30 p.m. on March 2, 1983, three chartered buses pulled up to the office tower. More than one hundred OPP officers, equipped with recording equipment, axes, sledgehammers, and a battering ram, rushed into Scientology’s offices. Acting on the findings of a secret two-year tax-fraud investigation of the church, they removed 900 boxes of material, among them illegally obtained confidential documents from government, medical, and police agencies. The church initially claimed the raid was spurred by attacks from the psychiatric community and believed it was entitled to Charter of Rights protection.

Hiring Clayton Ruby as its lawyer, Scientology pursued a decade-long fight against the raid and the charges that resulted from it. Some of its efforts were comical: in July 1988, the church offered to donate considerable sums to agencies working with drug addicts, the elderly, and the poor so long as theft charges were dropped. Ontario Attorney General Ian Scott rejected the offer, saying that “there’s no immunity that permits a church or anyone else to commit crimes in the country.” Ruby argued that the legal prosecution of a small religion like Scientology threatened the freedom of all faiths, and that while individual members may be guilty of offences, the whole church should not be held at fault.

The legal battle appeared over by 1992. When the seized boxes were returned that January, church members celebrated on Yonge Street. While a banner declaring “Scientology Wins after 9-year Battle” was draped across the building, a human chain passed the boxes back inside from a rented truck. Jubilation was short-lived: though acquitted of theft charges, the church and three of its members were found guilty of breach of trust. Related cases lingered for a few more years, including a libel case that earned crown attorney Casey Hill a then-record $1.6 million award from the church and one of its lawyers.

Even in the midst of its legal battles, the church gradually expanded its presence in 696 Yonge, filling space as other tenants departed. One of the last to go was the Brothers Restaurant and Tavern, which filled a streetfront space with vinyl booths and formica from 1979 to 2000. Operated by two brothers whose last names differed because of the phonetic spelling a government official wrote for one when they moved to Canada, Angelo Sfyndilis and Peter Sfendeles catered to a diverse clientele who appreciated their generous portions of comfort food. As Toronto Life noted in its obituary, “wherever you come from, wherever you’re going, Brothers has been a second home, a sheltering piece of smalltown Canadiana on a big, harsh anonymous street, in the middle of a big, harsh, anonymous city.” The Star praised Brothers’ “honest chicken sandwich,” while Now included it in its student survival guides for meals like the Little Brother Platter, which contained “eight thick slices of pastrami, eight of roast beef, four slabs of Canadian cheddar, a mound of potato salad, a mess of oil-and vinegar-drowned iceberg lettuce, a quartered dill pickle, and rings of pickled peppers.” When the lease was not renewed in 2000, deli items were replaced with copies of Dianetics.

Additional material from the January 25, 1972 edition of the Globe and Mail, the September 2, 1999 edition of Now, the May 2000 edition of Toronto Life, and the January 10, 1982, March 3, 1983, December 20, 1984, July 27, 1988, August 29, 1988, September 20, 1990, January 28, 1992, June 26, 1992, July 13, 2008, and January 24, 2013 editions of the Toronto Star.

|

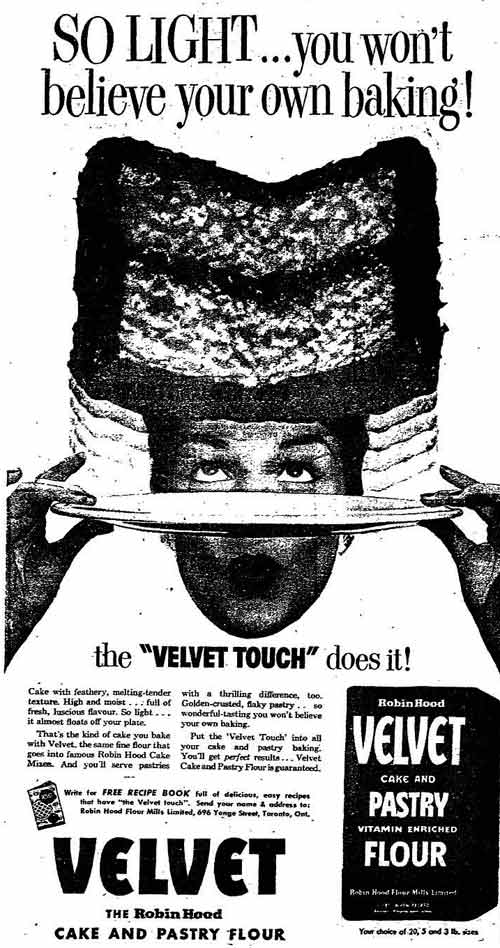

| Toronto Star, September 12, 1957. |

Built around 1955 in the International style of architecture, 696 Yonge’s initial tenant roster included recognizable brands like Avon cosmetics and Robin Hood flour. They were joined by an array of accounting firms, coal and mining companies, and the Belgian consulate, along with a number of construction and property management companies run by Samuel Diamond, whose name later graced the building.

By the 1970s, The Diamond companies were among the few original tenants remaining. Movie studio MGM settled in for a long stay, while the Ontario Humane Society teetered on the verge of financial ruin during its tenancy. There was a temporary office for a federal committee on sealing, which released a 1972 report recommending a temporary moratorium on seal hunting while solutions were sought to halt a population decline. The building even enjoyed a brief taste of religious controversies to come when the Unification Church—a.k.a. the “Moonies”—briefly opened an office, prompting questions about indoctrinated converts, growing wealth, and cult-like practices mirroring those later asked about the Church of Scientology.

L. Ron Hubbard’s religion, meanwhile, had shuffled around various sites in the city since the late 1950s, from meetings on Jarvis Street to a townhouse on Prince Arthur Avenue. The church’s reputation for defending itself grew as quickly as its membership—by the 1970s, official church statements were guaranteed to appear in the letters section within days of any faintly critical newspaper article. The Church of Scientology bought 696 Yonge in 1979.

|

| Toronto Star, March 3, 1983. |

Hiring Clayton Ruby as its lawyer, Scientology pursued a decade-long fight against the raid and the charges that resulted from it. Some of its efforts were comical: in July 1988, the church offered to donate considerable sums to agencies working with drug addicts, the elderly, and the poor so long as theft charges were dropped. Ontario Attorney General Ian Scott rejected the offer, saying that “there’s no immunity that permits a church or anyone else to commit crimes in the country.” Ruby argued that the legal prosecution of a small religion like Scientology threatened the freedom of all faiths, and that while individual members may be guilty of offences, the whole church should not be held at fault.

The legal battle appeared over by 1992. When the seized boxes were returned that January, church members celebrated on Yonge Street. While a banner declaring “Scientology Wins after 9-year Battle” was draped across the building, a human chain passed the boxes back inside from a rented truck. Jubilation was short-lived: though acquitted of theft charges, the church and three of its members were found guilty of breach of trust. Related cases lingered for a few more years, including a libel case that earned crown attorney Casey Hill a then-record $1.6 million award from the church and one of its lawyers.

|

| Now, September 2, 1999. The main article on cheap eats featured on this page was for the still-existing-and-still-cheap New York Subway on Queen Street. |

Additional material from the January 25, 1972 edition of the Globe and Mail, the September 2, 1999 edition of Now, the May 2000 edition of Toronto Life, and the January 10, 1982, March 3, 1983, December 20, 1984, July 27, 1988, August 29, 1988, September 20, 1990, January 28, 1992, June 26, 1992, July 13, 2008, and January 24, 2013 editions of the Toronto Star.

Comments