past pieces of toronto: the toronto mechanics' institute

From November 2011 through July 2012 I wrote the "Past Pieces of Toronto" column for OpenFile, which explored elements of the city which no longer exist. The following was originally posted on June 10, 2012.

For a building that launched one of Toronto’s greatest assets, the Toronto Mechanics’ Institute (TMI) had a history that historian Donald Jones once described as “disasterous.”

Established at a public meeting in 1830, the TMI (known as the York Mechanics’ Institute until 1834) was intended to provide for “the mutual improvement of mechanics and other who become members of the society in arts and sciences by the formation of a library of reference and circulation, by the delivery of lectures on scientific and mechanical subjects…and for conversation on subjects from which all discussion of political and religious matters is to be carefully excluded.” It was inspired by a wave of mechanics institutes established in Great Britain during the 1820s that aimed to educate the working classes. Since Toronto was barely industrialized in the 1830s, the organization’s early membership tended to be drawn from the middle class. Its early directors included prominent figures such as William Warren Baldwin, Sheriff William Jarvis, Jesse Ketchum and John Rolph. As historian J.M.S. Careless once noted, the TMI soon appeared to provide little more than “intellectual amusements” for its founding families. Regarding an early, well-publicized lecture on “Natural and Experimental Philosophy,” Careless suspected that “what any mechanics present may have thought of all this is something else.”

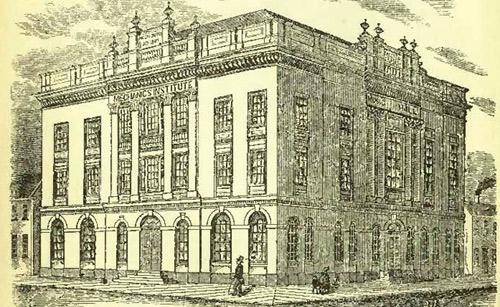

After meeting in various locations, the TMI purchased land for a permanent home at the northeast corner of Adelaide and Church Streets in 1853. Designed by the architectural firm of Cumberland and Storm, which had worked on the nearby St. James Cathedral, the building was nearly completed when construction stopped in mid-1855 due to a lack of funds. The grandiose design, which included a library, a two-floor amphitheatre-style lecture hall, and a grand music hall topped with paintings of the Muses, cost more than the money raised through public subscription drives and mortgages. For the next four years, the government of the Province of Canada rented the building as offices for the Crown Lands and Post Office departments. A government grant was used to finally complete the building in 1861.

Though it continued to offer educational programs, by the 1880s the TMI was viewed as a recreation centre. The Globe criticized it in 1881 for offering “a very poor library and an inadequate reading room accessible only to those who will pay a considerable entrance fee in advance.” At a special general meeting on March 28, 1883, the membership, which had barely reached 1,000, voted to hand over its assets and property to the City of Toronto to establish a public library. The move came nearly three months after voters had approved a bylaw authorizing municipal funding for such an institution.

Over the next year the building was reconfigured—the music hall

became the new reading room, while an addition was built along Adelaide

Street to provide room for up to 150,000 volumes. The date of the grand

opening of the first branch of the Toronto Public Library was specifically chosen: March 6, 1884—the 50th birthday of the city. At the opening ceremony, library board chairman John Hallam

apologized to the crowd that the facility wasn’t ready for prime

time—the reading rooms would open nearly two weeks later, while regular

circulation services didn’t commence for nearly a month. The crowd

didn’t mind, as they laughed while giving Hallam a loud round of

applause.

The collection quickly outgrew the building, resulting in the opening of the Central Reference Library (now the Koffler Student Centre) at College and St. George in 1906. The old TMI site remained a library branch until the late 1920s. After a short period of disuse, the building briefly housed a federal employment agency before being taken over by the City of Toronto’s Department of Public Welfare in 1931. The city used the premises for nearly two decades before it was demolished in 1950—only a historical plaque gives a hint of the site’s former identity and nothing about its past follies.

Additional material from A Century of Service: Toronto Public Library 1883-1983 by Margaret Penman (Toronto: Toronto Public Library Board, 1983), Lost Toronto by William Dendy (Toronto: McClelland and Stewart, 1993), and the March 5, 1988 edition of the Toronto Star.

|

| Source: Robertson's Landmarks of Toronto Volume 2. |

Established at a public meeting in 1830, the TMI (known as the York Mechanics’ Institute until 1834) was intended to provide for “the mutual improvement of mechanics and other who become members of the society in arts and sciences by the formation of a library of reference and circulation, by the delivery of lectures on scientific and mechanical subjects…and for conversation on subjects from which all discussion of political and religious matters is to be carefully excluded.” It was inspired by a wave of mechanics institutes established in Great Britain during the 1820s that aimed to educate the working classes. Since Toronto was barely industrialized in the 1830s, the organization’s early membership tended to be drawn from the middle class. Its early directors included prominent figures such as William Warren Baldwin, Sheriff William Jarvis, Jesse Ketchum and John Rolph. As historian J.M.S. Careless once noted, the TMI soon appeared to provide little more than “intellectual amusements” for its founding families. Regarding an early, well-publicized lecture on “Natural and Experimental Philosophy,” Careless suspected that “what any mechanics present may have thought of all this is something else.”

After meeting in various locations, the TMI purchased land for a permanent home at the northeast corner of Adelaide and Church Streets in 1853. Designed by the architectural firm of Cumberland and Storm, which had worked on the nearby St. James Cathedral, the building was nearly completed when construction stopped in mid-1855 due to a lack of funds. The grandiose design, which included a library, a two-floor amphitheatre-style lecture hall, and a grand music hall topped with paintings of the Muses, cost more than the money raised through public subscription drives and mortgages. For the next four years, the government of the Province of Canada rented the building as offices for the Crown Lands and Post Office departments. A government grant was used to finally complete the building in 1861.

Though it continued to offer educational programs, by the 1880s the TMI was viewed as a recreation centre. The Globe criticized it in 1881 for offering “a very poor library and an inadequate reading room accessible only to those who will pay a considerable entrance fee in advance.” At a special general meeting on March 28, 1883, the membership, which had barely reached 1,000, voted to hand over its assets and property to the City of Toronto to establish a public library. The move came nearly three months after voters had approved a bylaw authorizing municipal funding for such an institution.

|

| Source: the Toronto Star, March 5, 1988. |

The collection quickly outgrew the building, resulting in the opening of the Central Reference Library (now the Koffler Student Centre) at College and St. George in 1906. The old TMI site remained a library branch until the late 1920s. After a short period of disuse, the building briefly housed a federal employment agency before being taken over by the City of Toronto’s Department of Public Welfare in 1931. The city used the premises for nearly two decades before it was demolished in 1950—only a historical plaque gives a hint of the site’s former identity and nothing about its past follies.

Additional material from A Century of Service: Toronto Public Library 1883-1983 by Margaret Penman (Toronto: Toronto Public Library Board, 1983), Lost Toronto by William Dendy (Toronto: McClelland and Stewart, 1993), and the March 5, 1988 edition of the Toronto Star.

Comments