past pieces of toronto: subway interlining

From November 2011 through July 2012 I wrote the "Past Pieces of Toronto" column for OpenFile, which explored elements of the city which no longer exist. The following was originally posted on May 13, 2012.

When you mention lower Bay station, images conjured include an

abandoned subway platform used for film shoots, a TTC test lab, a Nuit Blanche installation venue or an occasional construction detour.

But when the Bloor-Danforth line opened in February 1966, lower Bay was

part of an experiment to allow riders to reach any destination without

transferring lines. The wye,

a triangular-shaped rail intersection that allowed interlining, proved

highly contentious among TTC officials during its six months of regular

service use.

The wye was among subway designer Norman Wilson’s recommendations when the Bloor-Danforth subway line was proposed in 1958. “The importance of this [wye] connection between the Bloor and University lines cannot be overstressed,” Wilson wrote. “It provides the utmost in flexibility to satisfy both present and future traffic demands. While this connection is expensive, it is of minimum possible length and of maximum possible utility both to subway passengers and to the carrying on of subway operations.” The wye was approved, but the eastern half of the junction as temporarily dropped from the project following an April 1960 vote of commissioners. The vote was inspired by recommendations from TTC operations Manager J.C. Inglis to remove half the wye due to costs and the potential to create delays throughout the system. Wilson resigned from the project, while an angry Metro Toronto Chairman Frederick Gardiner called a special meeting to demand an explanation for the TTC’s about-face. Several reports later, Metro Council approved the wye by a 21-3 vote on June 28, 1960.

When the Bloor-Danforth line began regular service on February 26, 1966, trains alternated between those that travelled straight across the line from Keele to Woodbine stations, and those that passed through the $14 million wye to loop through downtown along the Yonge-University line and end at Eglinton. Stations were equipped with bells and overhead flip signs to indicate which train was arriving. Delays were frequent early on due to signal problems and drivers who were too jittery to go through the wye. At times, all trains were stopped at the wye if one missed its scheduled entry time. Passengers were confused by the barrage of signage they faced, especially when determining the right platform to wait at on either level of Bay or St. George stations.

Within weeks, some municipal and TTC officials expressed concerns about the wye, some of which they claimed they had been told to keep quiet about during the approval phase. In a private meeting in early May 1966, TTC commissioners voted against ordering $6 million worth of new cars that would be required if interlining continued when extensions at both ends of the Bloor-Danforth line were opened within two years. Later that month the Star reported that 25 per cent of subway crews requested transfers to surface work because the holdups and the split-second scheduling required to send trains through the wye prevented employees from taking washroom breaks.

The wye had its defenders. Both the Globe and Mail and the Star published several editorials noting that the problem wasn’t the wye, but the refusal of the TTC to improve service. The Star declared that “what should be hammered into the heads of TTC brass is that their job is to serve the convenience of the public, not arrange the system so that it’s convenient for them.” While TTC commissioner Ford Brand had local media backing for his suggestion to operate the wye during rush hour only, the attitudes among its opponents within the transit provider hardened.

On June 23, 1966, computer punch cards were handed out to commuters to assess their service preferences, though the data collected also served as a travel pattern survey. The results showed that 15.6 per cent found the integrated system convenient, 16.1 per cent didn’t, and the rest didn’t care or weren’t affected. As Transit Toronto points out in an article on interlining, the survey was tilted to favour killing off line integration.

On September 5, 1966, separated subway service was introduced for a six-month trial, at the end of which the TTC would decide which service method would be permanently implemented. Lower Bay was closed, as St. George was returned to being the terminus of the Yonge-University line. The biggest complaint from riders was the lack of seats on trains leaving the transfer points. While the TTC claimed they received few complaints about the separated service, Brand claimed he received plenty of angry feedback about inconveniences, especially crowded platforms. When he tried to press these issues at a November 1966 TTC meeting, fellow commissioner Douglas Hamilton told Brand “you are too crusty, be quiet.”

As the separated line trial ended in early 1967, the TTC declined to reinstate interlining, citing costs and the effects of delays on the entire system. Despite the attempts of integrated service proponents like former mayor Allan Lamport (who believed the TTC operated under a balance sheet mentality), it never returned. The sign boxes were used to indicate short turns, then became little more than decoration. As Transit Toronto’s James Bow summed up the integrated subway system, “one has to wonder why they attempted it in the first place, rather than sabotaging it from the design phase on.”

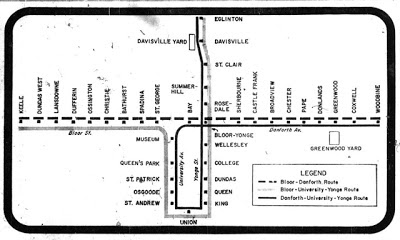

Additional material from the August 11, 1966 and November 2, 1966 editions of the Globe and Mail, and the February 26, 1966, May 18, 1966, June 1, 1966, June 4, 1966, March 4, 1967, and June 28, 1967 editions of the Toronto Star. Image: map of subway routes published in the February 25, 1966 edition of the Telegram.

|

| Map showing subway interlining. The Telegram, February 25, 1966. |

The wye was among subway designer Norman Wilson’s recommendations when the Bloor-Danforth subway line was proposed in 1958. “The importance of this [wye] connection between the Bloor and University lines cannot be overstressed,” Wilson wrote. “It provides the utmost in flexibility to satisfy both present and future traffic demands. While this connection is expensive, it is of minimum possible length and of maximum possible utility both to subway passengers and to the carrying on of subway operations.” The wye was approved, but the eastern half of the junction as temporarily dropped from the project following an April 1960 vote of commissioners. The vote was inspired by recommendations from TTC operations Manager J.C. Inglis to remove half the wye due to costs and the potential to create delays throughout the system. Wilson resigned from the project, while an angry Metro Toronto Chairman Frederick Gardiner called a special meeting to demand an explanation for the TTC’s about-face. Several reports later, Metro Council approved the wye by a 21-3 vote on June 28, 1960.

When the Bloor-Danforth line began regular service on February 26, 1966, trains alternated between those that travelled straight across the line from Keele to Woodbine stations, and those that passed through the $14 million wye to loop through downtown along the Yonge-University line and end at Eglinton. Stations were equipped with bells and overhead flip signs to indicate which train was arriving. Delays were frequent early on due to signal problems and drivers who were too jittery to go through the wye. At times, all trains were stopped at the wye if one missed its scheduled entry time. Passengers were confused by the barrage of signage they faced, especially when determining the right platform to wait at on either level of Bay or St. George stations.

Within weeks, some municipal and TTC officials expressed concerns about the wye, some of which they claimed they had been told to keep quiet about during the approval phase. In a private meeting in early May 1966, TTC commissioners voted against ordering $6 million worth of new cars that would be required if interlining continued when extensions at both ends of the Bloor-Danforth line were opened within two years. Later that month the Star reported that 25 per cent of subway crews requested transfers to surface work because the holdups and the split-second scheduling required to send trains through the wye prevented employees from taking washroom breaks.

The wye had its defenders. Both the Globe and Mail and the Star published several editorials noting that the problem wasn’t the wye, but the refusal of the TTC to improve service. The Star declared that “what should be hammered into the heads of TTC brass is that their job is to serve the convenience of the public, not arrange the system so that it’s convenient for them.” While TTC commissioner Ford Brand had local media backing for his suggestion to operate the wye during rush hour only, the attitudes among its opponents within the transit provider hardened.

On June 23, 1966, computer punch cards were handed out to commuters to assess their service preferences, though the data collected also served as a travel pattern survey. The results showed that 15.6 per cent found the integrated system convenient, 16.1 per cent didn’t, and the rest didn’t care or weren’t affected. As Transit Toronto points out in an article on interlining, the survey was tilted to favour killing off line integration.

On September 5, 1966, separated subway service was introduced for a six-month trial, at the end of which the TTC would decide which service method would be permanently implemented. Lower Bay was closed, as St. George was returned to being the terminus of the Yonge-University line. The biggest complaint from riders was the lack of seats on trains leaving the transfer points. While the TTC claimed they received few complaints about the separated service, Brand claimed he received plenty of angry feedback about inconveniences, especially crowded platforms. When he tried to press these issues at a November 1966 TTC meeting, fellow commissioner Douglas Hamilton told Brand “you are too crusty, be quiet.”

As the separated line trial ended in early 1967, the TTC declined to reinstate interlining, citing costs and the effects of delays on the entire system. Despite the attempts of integrated service proponents like former mayor Allan Lamport (who believed the TTC operated under a balance sheet mentality), it never returned. The sign boxes were used to indicate short turns, then became little more than decoration. As Transit Toronto’s James Bow summed up the integrated subway system, “one has to wonder why they attempted it in the first place, rather than sabotaging it from the design phase on.”

Additional material from the August 11, 1966 and November 2, 1966 editions of the Globe and Mail, and the February 26, 1966, May 18, 1966, June 1, 1966, June 4, 1966, March 4, 1967, and June 28, 1967 editions of the Toronto Star. Image: map of subway routes published in the February 25, 1966 edition of the Telegram.

Comments