past pieces of toronto: the shell oil/bulova tower

From November 2011 through July 2012 I wrote the "Past Pieces of Toronto" column for OpenFile, which explored elements of the city which no longer exist. The following was originally posted on March 4, 2012.

Oil can giveth, and oil can taketh away. That might be the easiest way to sum up the story of the 36-metre-high clock tower

that provided Canadian National Exhibition visitors with a great view

of the city and a foolproof meeting spot for 30 years. Born from

sponsorship by an oil giant, the landmark died to make way for a car race.

Designed by architect George Robb, the modernist Shell Oil Tower was the first building in Toronto to utilize welded-steel construction. It quickly proved a popular attraction following its debut in 1955, thanks to promotional pitches like this one:

The tower provided an easily identifiable place for families to meet at the fair even after changes during the 1960s and 1970s saw the installation of a digital clock face and a sponsorship switch from Shell to Bulova. A year after the tower was demolished confusion reigned as parents, used to its presence and conditioned by advertisements, continued to tell their kids to meet there, which led to a rise in visitors to the fair’s Lost Children Office.

The Shell tower’s future was in doubt before it reached its 20th birthday due to a report that recommended it be demolished along with a dozen other buildings to make way for a revamped Exhibition Place. While some elements of the plan were eventually enacted (a giant trade centre), proposals such as an athletic complex, aquarium or city history museum proved a spectre and probably helped contribute to the tower’s slow decay. Elevator breakdowns grew more frequent—in one incident five teens trapped for one-and-a-half hours were rewarded with free popsicles for their misery (to which one teen responded “Big deal. You can get them free inside the Food Building”). After the elevators and staircases were declared unsafe, the tower closed in 1983.

When plans for the first Molson Indy were devised, the tower site was deemed attractive for a pit stop. CNE officials willing to tear the tower down to meet Molson’s demands stated that the $500,000 required to repair the structure would be better spent on other facilities. Among the local architects, preservationists and urban activists who criticized the impending demolition was Jane Jacobs, who told the Star that it ominously indicated “a resurgence of the ruthless attitude toward existing buildings and monuments that was so prevalent during the ’60s and ’70s. The tower is something we can afford to keep for its own sake and the fact it ties people to memories. It has associations for many people in the city.”

Despite the cases made for its architectural and landmark value, and a proposal to move it elsewhere on the grounds, the tower came down in November 1985. Its demise prompted a wave of interest in preserving contemporary architecture, notably the Toronto Modern: Architecture book and exhibition in 1987. Now, if somebody on the CNE grounds asked you to meet them at the tower, you’d be checking the streetcar schedule for the next trip toward the CN Tower.

Additional material from the September 3, 1981 edition of the Globe and Mail, and the August 22, 1955, November 8, 1985, and August 26, 1986 editions of the Toronto Star.

|

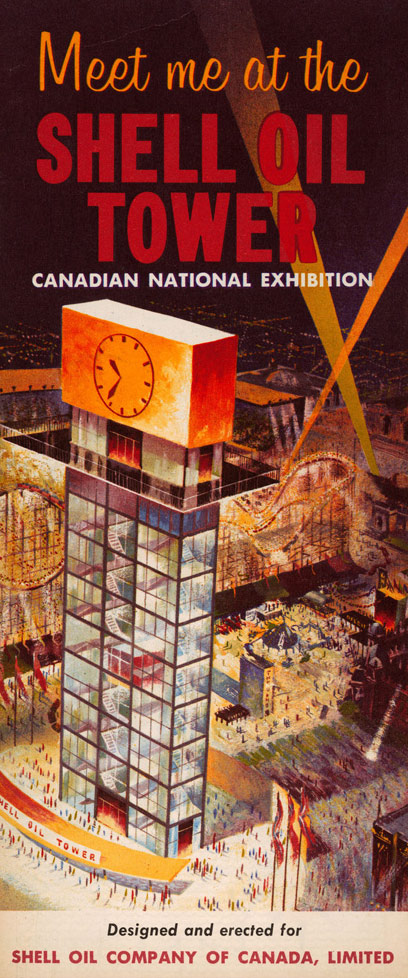

| “Meet me at the Shell Tower” pamphlet, circa 1955, City of Toronto Archives, Fonds 261, Series 756, File 50, Item 1. |

Designed by architect George Robb, the modernist Shell Oil Tower was the first building in Toronto to utilize welded-steel construction. It quickly proved a popular attraction following its debut in 1955, thanks to promotional pitches like this one:

There’s a new landmark at the “Ex.” It’s the Shell Oil Tower, whose gleaming glass walls and giant clock add a new feature to the skyline. An elevator is waiting to whisk you to the observation platform, far above the ground, where you can look down on the breathtaking spectacle of the greatest show on earth, the Canadian National Exhibition...look out over Metropolitan Toronto. Here is a unique bird’s eye view which makes a trip up the Shell Tower a must for every visitor to the Exhibition. You’ll find the Shell Tower straight through the Princes’ Gates. Make it a meeting place—get into the habit of saying to your friends “Meet me at the Shell Oil Tower.”

The tower provided an easily identifiable place for families to meet at the fair even after changes during the 1960s and 1970s saw the installation of a digital clock face and a sponsorship switch from Shell to Bulova. A year after the tower was demolished confusion reigned as parents, used to its presence and conditioned by advertisements, continued to tell their kids to meet there, which led to a rise in visitors to the fair’s Lost Children Office.

The Shell tower’s future was in doubt before it reached its 20th birthday due to a report that recommended it be demolished along with a dozen other buildings to make way for a revamped Exhibition Place. While some elements of the plan were eventually enacted (a giant trade centre), proposals such as an athletic complex, aquarium or city history museum proved a spectre and probably helped contribute to the tower’s slow decay. Elevator breakdowns grew more frequent—in one incident five teens trapped for one-and-a-half hours were rewarded with free popsicles for their misery (to which one teen responded “Big deal. You can get them free inside the Food Building”). After the elevators and staircases were declared unsafe, the tower closed in 1983.

When plans for the first Molson Indy were devised, the tower site was deemed attractive for a pit stop. CNE officials willing to tear the tower down to meet Molson’s demands stated that the $500,000 required to repair the structure would be better spent on other facilities. Among the local architects, preservationists and urban activists who criticized the impending demolition was Jane Jacobs, who told the Star that it ominously indicated “a resurgence of the ruthless attitude toward existing buildings and monuments that was so prevalent during the ’60s and ’70s. The tower is something we can afford to keep for its own sake and the fact it ties people to memories. It has associations for many people in the city.”

Despite the cases made for its architectural and landmark value, and a proposal to move it elsewhere on the grounds, the tower came down in November 1985. Its demise prompted a wave of interest in preserving contemporary architecture, notably the Toronto Modern: Architecture book and exhibition in 1987. Now, if somebody on the CNE grounds asked you to meet them at the tower, you’d be checking the streetcar schedule for the next trip toward the CN Tower.

Additional material from the September 3, 1981 edition of the Globe and Mail, and the August 22, 1955, November 8, 1985, and August 26, 1986 editions of the Toronto Star.

Comments